When a catastrophic event strikes, businesses expect their insurance policies to respond as promised, yet the fine print of these complex documents can become a battleground where verbal understandings clash with written terms. This analysis delves into the critical legal principle that the explicit language of a written contract supersedes any alleged unwritten agreements, particularly in high-stakes insurance disputes. The central questions are: what is the stringent legal standard required to reform a policy based on a mutual mistake, and how do courts balance the concrete text of a policy against claims of a shared, but undocumented, understanding between insurer and policyholder?

The examination of this principle is not merely academic; it is grounded in a real-world conflict with millions of dollars on the line. At the heart of this issue is the struggle to determine whether an insurer can retroactively alter a policy’s terms to include an exclusion that was never put into writing. This situation forces a legal showdown, pitting the policyholder’s reliance on the printed word against the insurer’s assertion of a mutual, unwritten intent, a scenario that tests the very foundation of contract law.

The Centrality of Explicit Policy Language Over Unwritten Understandings

The legal system consistently prioritizes the written word in contractual disputes, operating on the foundational premise that a signed agreement represents the complete and final understanding between parties. In the context of insurance, this means that the policy document itself is the primary source of truth regarding coverage, terms, and exclusions. When an insurer argues that a policy should be reformed—or retroactively rewritten—to reflect a supposed verbal agreement, they face a significant uphill battle. This is because courts are inherently reluctant to alter the clear terms of a contract, as doing so could undermine the certainty and predictability that commercial agreements are meant to provide.

To overcome this judicial deference to the written contract, an insurer must prove a “mutual mistake,” a legal doctrine that requires demonstrating with “clear and convincing evidence” that both parties were operating under the same erroneous assumption when the policy was executed. This standard is intentionally high to prevent parties from escaping their contractual obligations by later claiming the agreement did not reflect their true intentions. The challenge for the insurer is not just to show that they intended for an exclusion to apply, but that the policyholder shared this exact same mistaken belief, a task that becomes nearly impossible when the policyholder’s actions suggest otherwise.

Background of the PrairieGold Solar v. AGCS Marine Insurance Dispute

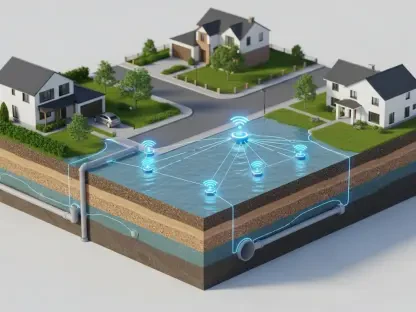

This legal analysis originates from a coverage dispute involving PrairieGold Solar LLC and its insurers, led by AGCS Marine Insurance Company. The conflict arose after PrairieGold’s solar facility in Puerto Rico sustained significant damage during Hurricane Maria in 2017, leading the company to file a claim under its 2014 “all-risk” insurance policy. The insurers denied the claim, arguing that despite the policy’s silence on the matter, both parties understood that losses from natural catastrophes like hurricanes were excluded. This set the stage for a legal fight over whether an unwritten understanding could override explicit policy terms.

The case carries substantial importance for the commercial insurance market because it directly confronts the enforceability of unwritten exclusions. In an industry built on precisely worded contracts and risk assessment, the outcome of such a dispute has far-reaching consequences. It forces a critical examination of an insurer’s ability to retroactively modify a policy based on alleged verbal understandings, highlighting the immense legal and evidentiary hurdles they face when the policy documents do not support their position. This makes the case a crucial benchmark for how courts treat the sanctity of the written word in sophisticated commercial transactions.

Research Methodology Findings and Implications

Methodology

This analysis is rooted in a thorough review of the legal record from the PrairieGold v. AGCS litigation. The primary sources include the initial dismissal of the case by the lower court, the subsequent unanimous reversal by the appellate court, and the detailed legal briefs and arguments submitted by both PrairieGold and its insurers. This documentary review provides a comprehensive view of the evidence presented and the legal reasoning applied at each stage of the dispute.

The core of the methodology involves a close examination of the legal standard for contract reformation. Specifically, the analysis focuses on how the appellate court interpreted and applied the requirement for “clear and convincing evidence” of a mutual mistake. By dissecting the court’s reasoning, this research illuminates why the insurer’s evidence was deemed insufficient and how the judiciary prioritizes unambiguous policy text over extrinsic evidence of intent, such as negotiation history or alleged verbal agreements.

Findings

The principal finding of this research is the appellate court’s decisive rejection of the insurer’s attempt to reform the insurance policy. The court ruled that the evidence presented by the insurer fell far short of the high standard required to prove a mutual mistake. The explicit language of the policy, which did not contain an exclusion for named storms like Hurricane Maria, was found to be the governing factor. The judges were not persuaded that a shared, unwritten understanding to exclude such perils ever existed.

Key evidence highlighted in the ruling dismantled the insurer’s argument. Testimony from a PrairieGold representative revealed that the company believed its primary policy already covered major storms and, for that reason, consciously declined to purchase a separate, expensive policy add-on designed for lesser perils. This position was unexpectedly bolstered by an insurer’s employee, who admitted under oath that it was her impression that PrairieGold believed it had coverage for named windstorms. This combination of explicit policy text and corroborating testimony proved fatal to the insurer’s claim of a mutual mistake.

Implications

The most significant practical implication for the insurance industry is the reinforcement of a fundamental principle: all intended exclusions must be articulated clearly and explicitly within the policy documents. The PrairieGold ruling serves as a powerful caution against relying on underwriting notes, negotiation history, or alleged common understandings to limit coverage. Insurers must ensure that the final policy language precisely reflects their underwriting intent, as courts are unlikely to rewrite the contract for them after a loss occurs.

For policyholders, the decision affirms the strength and reliability of the written contract. It demonstrates that when a policy is clear on its face, it will be enforced as written, even in complex, high-value commercial disputes. The ruling establishes a strong precedent that sophisticated commercial entities are held to the precise terms of the agreements they sign. Consequently, it becomes exceedingly difficult for an insurer to later introduce extrinsic evidence to contradict unambiguous policy language and deny a claim based on an alleged unwritten intention.

Reflection and Future Directions

Reflection

The primary obstacle for the insurers in this case was the exceptionally high legal bar for contract reformation. Their efforts to prove a mutual understanding were ultimately counterproductive; instead of providing the “clear and convincing evidence” the court required, their submissions were found to introduce further factual disputes and ambiguity. The evidence intended to clarify the parties’ intent only served to highlight their differing interpretations of the coverage, thereby undermining the very premise of a “mutual” mistake.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this analysis. While the appellate ruling is a significant legal development, it is not the final word on whether PrairieGold’s claim will be paid. The decision was procedural, focused solely on reversing the lower court’s dismissal and rejecting the reformation argument. The case now returns to the lower court for further proceedings, meaning the scope of this research is confined to the specific issue of contract reformation rather than the ultimate outcome of the coverage dispute.

Future Directions

Future research should closely monitor the final resolution of this case as it proceeds in the lower court. The focus will now shift from reformation to the direct interpretation of the policy’s existing language, which promises to generate further valuable insights into how courts handle all-risk policies and coverage for catastrophic events. Tracking this outcome will provide a more complete picture of the dispute’s impact.

Furthermore, this case warrants broader exploration into a growing trend in insurance litigation where insurers attempt to introduce evidence of underwriting intent or prior negotiations to contradict clear policy text. A comparative study of similar cases across different jurisdictions could reveal patterns in judicial reasoning and identify best practices for both insurers and policyholders. Such research would contribute significantly to understanding the evolving dynamics of contract interpretation in the insurance sector.

Conclusion The Enduring Power of the Written Contract

The PrairieGold case ultimately underscored a foundational principle of contract law: the written word of an insurance policy is paramount. The appellate court’s refusal to reform the contract without overwhelming evidence of a shared mistake was a decisive moment. It sent a powerful reminder to carriers and underwriters that the terms memorialized in a signed policy carry immense legal weight, and attempts to retroactively alter them based on memory or informal understandings are likely to fail.

In the end, this dispute reaffirmed that clarity and precision in drafting policy language are not just best practices but essential safeguards. The ultimate lesson from this legal battle is unequivocal. If an exclusion is critical enough to shape the entire scope of a risk agreement, it must be stated in writing. In the eyes of the court, an exclusion that exists only in theory, but not in text, may not exist at all.