I’m thrilled to sit down with Simon Glairy, a renowned expert in insurance and InsurTech, with deep expertise in risk management and AI-driven risk assessment. With years of experience navigating complex fraud cases and emerging technologies, Simon offers unparalleled insights into the evolving landscape of insurance litigation. Today, we’re diving into a high-profile Louisiana insurance fraud case involving an alleged staged trucking accident, exploring its implications for the industry, the legal intricacies, and what it means for fraud detection moving forward.

Can you walk us through the core details of this Louisiana insurance fraud case involving a trucking accident?

Absolutely. This case revolves around a collision that occurred on July 17, 2018, in New Orleans between a Ford Mustang and an 18-wheeler. The Mustang was driven by Anthony Straughter, with Deron Alexander and Russell Bickham as passengers, while the truck was operated by Aaron Matthew White on behalf of The Trinity System, Inc. The plaintiffs sued White, Trinity, and Wilshire Insurance Company, claiming White was at fault while acting in the scope of his employment. What makes this case stand out is the defendants’ later assertion that the accident was staged as part of a scheme to defraud insurers, leading to a legal battle over millions in awards and settlements.

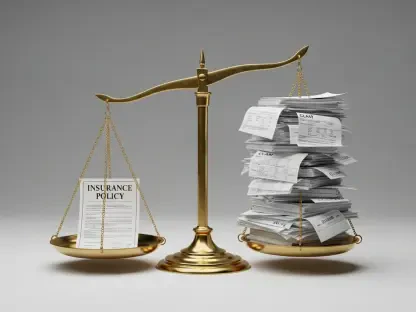

What can you tell us about the initial jury awards and the claims made by the plaintiffs?

The jury awarded significant sums to the plaintiffs after the trial. Straughter received $985,000, while Alexander was awarded $2,390,000. The plaintiffs’ claims hinged on the argument that the truck driver, White, was negligent and responsible for the accident, causing them injuries and damages. These hefty awards set the stage for the defendants’ pushback, as they believed the incident wasn’t a genuine accident but rather a deliberate setup to secure payouts from the insurance company.

Why did the defendants argue that the accident was staged, and what evidence supported their position?

The defendants sought to annul the judgments and settlement because they uncovered evidence suggesting the crash was orchestrated. They pointed to phone records that linked the plaintiffs to Cornelius Garrison, a figure tied to a federal investigation called “Operation Sideswipe,” which focused on staged accidents involving commercial vehicles in Orleans Parish. These records, found in medical documents and the accident report, showed communications with Garrison on the day of the crash, raising red flags about a coordinated fraud scheme targeting insurers.

How does this case tie into the broader federal investigation you mentioned?

“Operation Sideswipe” is a federal probe into a pattern of staged motor vehicle accidents, particularly those involving commercial trucks, in the New Orleans area. The investigation has uncovered networks of individuals allegedly working together to fake collisions and file fraudulent claims for personal injury and damages. In this case, the connection to Garrison, who was indicted as part of that operation, provided the defendants with a basis to argue that the plaintiffs were part of a larger criminal effort to exploit insurance companies, which is why they pushed to have the judgments thrown out.

What was the trial court’s reasoning for initially dismissing the defendants’ petition to annul the judgments?

The trial court dismissed the petition because they believed the defendants waited too long to file it. Under Louisiana law, there’s a one-year peremptive period to challenge a judgment based on fraud, and the court ruled that the defendants had enough suspicion of fraud as early as May 2021. This suspicion came from their own discovery responses noting similarities to other accidents under federal scrutiny. Because the petition wasn’t filed within that one-year window from 2021, the court found it untimely and refused to revisit the case.

How did the Louisiana Court of Appeal see the timing issue differently?

The Fourth Circuit took a different view on when that one-year clock started ticking. They ruled that mere suspicion of fraud isn’t enough to trigger the peremptive period. Instead, it begins only when there’s concrete knowledge of facts that would prompt further inquiry. The appellate court determined that the defendants didn’t have sufficient evidence until March 2023, when they connected the plaintiffs to Garrison through phone records. Since the petition was filed within a year of that discovery, the court found it timely, reversed the dismissal, and sent the case back for further review.

What does it mean for the case to be remanded to the trial court, and what’s the next step?

Remanding the case means it’s being sent back to the trial court for a full examination of the fraud allegations on their merits. The appellate court’s ruling wasn’t about whether fraud occurred but whether the defendants had the right to challenge the judgments based on timing. Now, the trial court will dive into the substance of the claims—looking at the evidence of a staged accident, the phone records, and the connection to Garrison—to decide if the original judgments and settlement should be annulled. It’s a critical phase that could reshape the outcome.

Why do you think this case matters so much to professionals in the insurance industry?

This case is a wake-up call for the insurance industry, especially for those handling commercial auto claims. It highlights the sophistication of potential fraud schemes and the importance of thorough investigation early on. Insurers need to be proactive in spotting red flags, like unusual patterns in claims or connections to known fraud rings. It also underscores the legal challenges of timing—knowing when to act on suspicions of fraud before procedural deadlines close the door. Beyond that, it’s a reminder of how costly and complex these disputes can become, pushing the need for better fraud detection tools and strategies.

Looking ahead, what is your forecast for the impact of cases like this on insurance fraud prevention?

I think cases like this will drive a significant shift in how the insurance industry approaches fraud prevention. We’re likely to see greater investment in technology, like AI and data analytics, to identify suspicious patterns in claims data before they escalate into multimillion-dollar lawsuits. There’ll also be a push for tighter collaboration between insurers, law enforcement, and legal teams to tackle organized fraud rings more effectively. On the legal side, I expect courts to refine how they interpret timing rules in fraud challenges, potentially giving defendants more leeway to uncover hidden schemes. Ultimately, the focus will be on staying one step ahead of increasingly sophisticated fraudsters.