We’re joined today by Simon Glairy, a recognized expert in insurance and Insurtech, whose work on risk management and regulatory policy offers a critical perspective on one of the most embattled insurance markets in the country. California’s property insurance landscape is in turmoil, with major carriers retreating from high-risk areas, leaving homeowners with few options. In response, lawmakers are pushing a significant overhaul of the state’s insurer of last resort, the FAIR Plan. We’ll explore the catalysts behind this long-overdue reform, the practical struggles homeowners face with bare-bones coverage, and whether these changes can genuinely stabilize the market or simply enlarge the state’s safety net. We’ll also touch on the delicate balance between expanding coverage and maintaining affordability, and the crucial financial guardrails needed to prevent the plan from undermining the private market it was designed to support.

Regulators are now citing systemic failures in the FAIR Plan, though some of these issues were identified in a 2022 operational assessment. What specific catalysts finally pushed this reform forward, and what does this long delay reveal about the challenges of regulating quasi-public entities like this?

The momentum we’re seeing now is really a perfect storm of regulatory findings, public pressure, and catastrophic events. The December 2025 “Report of Examination” from the Department of Insurance was the official trigger, with Commissioner Lara calling out what he termed “systemic failures.” But let’s be clear, these aren’t new problems. The fact that many of these 17 “critical recommendations” stem from a 2022 assessment that was largely ignored is incredibly telling. The real catalysts were the devastating 2025 Los Angeles wildfires, which laid bare the plan’s inability to handle a large-scale event, and the subsequent media scrutiny, including a CBS News investigation that questioned the plan’s secrecy. The long delay highlights the inherent inertia in regulating these quasi-public entities; they often operate in a grey area, and it takes a major crisis and public outcry to force an uncomfortable but necessary evolution.

FAIR Plan policies often exclude liability and offer only actual cash value up to $3 million, creating gaps for homeowners. Can you walk us through the practical difficulties and financial risks homeowners in high-value areas face when relying on this bare-bones coverage and complex wraparound policies?

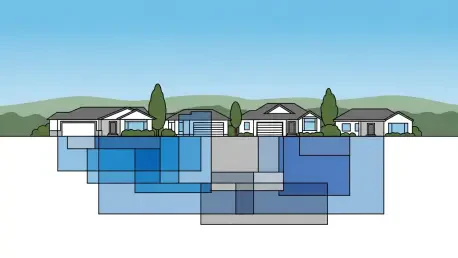

The reality for these homeowners is a constant state of financial anxiety. Imagine owning a home in a community like Malibu or Pacific Palisades where the land value alone is enormous, and being told your only option is a policy that won’t even cover the cost to rebuild. The $3 million cap on actual cash value is a drop in the bucket for many. This forces them and their brokers into a frantic scavenger hunt for supplemental coverage. They have to piece together a Difference in Conditions, or DIC, policy from the surplus lines market, assuming one is even available. This creates a patchwork of protection that can be confusing, expensive, and riddled with its own gaps. You might have two different adjusters from two different companies pointing fingers at each other after a loss. It’s an incredibly stressful and precarious way to protect what is likely your family’s most significant asset.

Some critics argue this bill won’t solve the core problem of insurance availability. Beyond reforming the FAIR Plan, what fundamental market or regulatory changes are truly necessary to persuade private insurers like State Farm and Allstate to begin writing new policies again in high-risk regions?

This is the central issue, and you’re right, the Make it FAIR Act is a necessary but insufficient step. It’s essentially patching a lifeboat while the ship is still taking on water. The fundamental reason carriers like State Farm and Allstate have pulled back is that the state’s regulatory environment has not allowed them to price for the actual risk they are taking on, particularly with wildfire exposure. To bring them back, California needs to address rate adequacy. This means allowing insurers to use forward-looking catastrophe models in their rate filings, rather than relying solely on historical data that no longer reflects our climate reality. Without the ability to charge premiums that are commensurate with the risk, private capital will simply not re-enter the market in a meaningful way, and the FAIR Plan will continue to be the only option for a growing number of Californians.

The legislation aims to reform claims handling, especially after disputes over smoke and ash damage. What specific operational changes must the FAIR Plan make to fairly assess “direct physical loss” from wildfires, and what metrics should regulators use to ensure real improvement in accountability for homeowners?

The disputes over smoke and ash damage are a perfect example of where the process breaks down. Homeowners are left with contaminated properties, yet claims are denied because there are no visible flames. The FAIR Plan must first establish clear, consistent, and scientifically-grounded standards for what constitutes “direct physical loss” from a wildfire, explicitly including pervasive smoke and ash. This requires investing in specialized training for adjusters and creating transparent protocols for testing and remediation. For regulators, the metrics for success can’t just be about closing claims faster. They need to track the rate of claim denials for smoke and ash, audit the consistency of settlement offers, and monitor the volume of lawsuits filed against the plan. True accountability means seeing those numbers trend in the right direction and ensuring families aren’t being forced to sue to get a fair outcome.

Expanding FAIR Plan coverage to resemble a standard policy will almost certainly increase premiums. How can this be structured to remain affordable for consumers, and what is the risk that a larger, more expensive FAIR Plan could further destabilize the private insurance market?

This is the tightrope regulators have to walk. You can’t just flip a switch and offer an HO-3 policy at the old fire-only price; the math doesn’t work. The increased premiums are inevitable. One way to structure this could be a tiered or modular approach, allowing homeowners to select and pay for the specific coverages they need, like liability or water damage, rather than a one-size-fits-all expansion. However, the greater risk is one of market dynamics. If the FAIR Plan becomes too comprehensive, it starts to look less like a backstop and more like a state-run competitor. If its pricing, even when higher, is perceived as being artificially suppressed by the state, it could disincentivize private insurers from ever returning, effectively crowding them out for good and making the “insurer of last resort” the insurer of permanent necessity.

Industry groups warn that mandating broader coverage could “balloon” the FAIR Plan, putting all Californians at risk for future shortfalls. What are the key financial or governance guardrails needed to prevent this expansion from undermining the goal of restoring a healthy private insurance market?

The industry’s concern about the plan “ballooning” is valid. A larger plan means concentrated risk, and a major catastrophe could lead to massive assessments on all policyholders in the state. The most critical guardrail is ensuring the FAIR Plan is actuarially sound. Premiums for any expanded coverage must be adequate to build sufficient reserves to pay future claims without relying on post-event bailouts. On the governance side, the reforms must bring true transparency and oversight. This means independent audits, public board meetings, and clear lines of accountability to prevent the kind of operational neglect we saw after the 2022 recommendations. Finally, there needs to be a clear and aggressive “depopulation” strategy—a formal mechanism to move policies from the FAIR Plan back to the private market as soon as a willing private insurer is found. Without that off-ramp, the plan is destined to grow indefinitely.

What is your forecast for California’s property insurance market?

My forecast is one of cautious, and frankly, painful, transition. In the short term, the FAIR Plan will continue to grow as these reforms are debated and implemented. AB 1680 is a critical effort to make that growth more manageable and the plan more responsive to consumers, but it doesn’t address the core disease, which is the lack of a viable private market. The market’s long-term health is entirely dependent on whether the state can stomach the difficult political decision to allow for risk-based pricing. If they can modernize their rate-setting regulations, we may see a slow, tentative return of private carriers over the next few years. If they don’t, California is on a path toward a de facto state-run insurance system for high-risk areas, with all the financial instability that implies. The next 18 to 24 months will be absolutely pivotal.