In a landscape dominated by discussions of artificial intelligence and quantum computing, it is the centuries-old legal contract that continues to define the most significant risks for technology companies and their insurers. Despite the dizzying pace of technological innovation, the core principles of underwriting technology Errors & Omissions (E&O) insurance have remained remarkably stable. While new and complex risks constantly emerge from cloud computing, AI, and the ever-expanding Internet of Things, underwriters find that the most potent exposures are often not hidden within intricate lines of code but are plainly written in the language of client agreements. The central focus for insurers remains steadfast: assessing how the failure of a company’s product or service could inflict financial harm upon a third party. This foundational principle of liability has proven remarkably durable, providing a consistent lens through which to evaluate risk even as the technology itself has been completely transformed into something unrecognizable from a decade ago.

The Unchanging Core in a Changing Tech World

The fundamental objective of a technology E&O underwriter today remains strikingly similar to what it was in the early days of the digital revolution: to evaluate the financial liability that arises when a product or service fails to perform as promised. Whether the technology in question is a sophisticated AI algorithm powering a financial market, an embedded software component in a critical IoT device, or a cloud-native SaaS platform serving millions, the core underwriting question persists. What is the potential financial consequence for a customer if this technology breaks, falters, or delivers an incorrect result? This enduring focus on third-party financial loss serves as the consistent framework through which all new technologies are assessed. It demonstrates that while the delivery mechanisms and capabilities of technology have evolved exponentially, the foundational risks of professional negligence and service failure have not been fundamentally altered, providing a stable anchor in a sea of constant change.

While the fundamental nature of the risk has not changed, its context and potential magnitude have shifted dramatically, driven primarily by the explosion of digital connectivity. This has created a vast, intricate web of interdependent systems where insurers are no longer just evaluating the risk of a single, isolated error. A primary focus has now shifted to “aggregation risk”—the immense potential for a single failure to cascade through countless interconnected systems, causing widespread and correlated disruption. The “downstream impact” of an outage or a vulnerability in a widely used cloud service or an embedded technology component has become a central point of analysis. A single incident at one provider can trigger a multitude of claims from various affected parties, turning a localized problem into a systemic event. This has made evaluating the potential blast radius of a failure as critical, if not more so, than assessing the initial product itself.

The Blurring Lines of Liability and Security

In recent years, insurers have significantly intensified their scrutiny of a technology company’s internal cybersecurity practices, marking a notable evolution in underwriting philosophy. The post-pandemic approach has moved beyond simply asking how a company’s failure could harm others to demanding to know, “How have they protected their own house?” This involves a granular and often unforgiving review of a firm’s security posture, from its incident response plans to its specific technological controls. This shift has led to the establishment of clear, non-negotiable security standards. Multi-factor authentication (MFA), once considered a best practice, has transitioned into a baseline requirement for insurability across the industry. Insurers have adjusted their pricing, terms, and even their appetite to write coverage based on its presence, and the industry is already looking ahead. Experts predict that Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) and Managed Detection and Response (MDR) solutions will soon become “the new MFA”—the next set of essential controls underwriters will expect to see firmly in place.

For a majority of technology clients, the practical distinction between E&O and cyber liability has become increasingly blurred, to the point where the terms are often used interchangeably. This reflects the modern reality that a single event, such as a major data breach or a prolonged system outage, can simultaneously trigger both first-party losses for the tech company (cyber) and third-party liability claims from its clients (E&O). In response to this convergence, insurers frequently bundle these coverages into a single, integrated policy. This dual perspective requires underwriters to concurrently assess a company’s ability to protect itself from attacks and its contractual responsibility for protecting its clients from the consequences of its service failures. This can lead to highly complex claims scenarios, such as an IT consultant being held liable for recommending a third-party security vendor that subsequently suffers a major failure, underscoring the intricate and often hidden supply chain risks inherent in the modern technology ecosystem.

Navigating New Frontiers and Established Risks

Artificial intelligence represents one of the most significant and ambiguous emerging risks for technology companies and their insurers. The widespread and rapid adoption of AI has far outpaced the development of a corresponding legal and regulatory framework, creating profound uncertainty for underwriters in several key areas. Without established case law and clear regulations, it becomes exceptionally difficult to price the exposure, forecast potential claims, and determine how existing policy language will respond to novel AI-related failures like algorithmic bias, inaccurate outputs, or intellectual property infringement. This uncertainty is also fueling a new debate about where AI-related risks should reside within a company’s insurance portfolio. Brokers are increasingly asking whether liability should fall under a Directors & Officers (D&O) policy, covering management decisions like deploying a risky AI model, or an E&O policy, covering the failure of the AI product itself. The industry may move toward resolving this ambiguity by creating blended D&O/E&O policies.

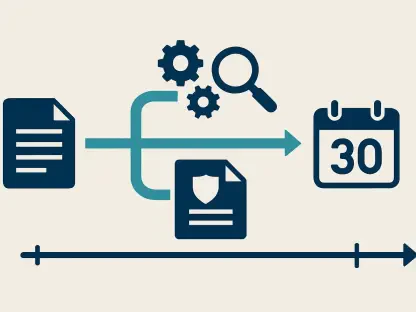

Despite the industry’s intense focus on new threats like AI and systemic cyber events, the core argument remains that a breach of contract is the most significant and fundamental exposure for any technology client. Consequently, rigorous contract analysis serves as the bedrock of tech E&O underwriting, particularly for mid-market and large enterprise accounts where a thorough review is standard practice. Underwriters meticulously scrutinize contracts for specific “red flags” that can dramatically increase an insured’s liability and transfer an unacceptable level of risk to the carrier. These include limitation of liability clauses tied directly to the insurance policy limits, vague or overly broad warranty statements that “promise the moon and the stars,” a failure to explicitly disclaim liability for consequential damages like a customer’s lost profits, and one-sided indemnification clauses that can force a company to pay for damages it did not directly cause.

A Reckoning with Systemic Threats

Recent years saw a notable increase in widespread, systemic outages caused by both malicious actors and internal errors, with major incidents affecting critical services that demonstrated the potential for a single point of failure to cause large-scale disruption and generate massive, correlated claims. This trend forced insurers to re-evaluate how they modeled risk and led to significant impacts on market pricing, capacity, and coverage terms. Ultimately, it was understood that the greatest threat to a technology company was often something entirely unforeseen. Unlike natural catastrophes, which could be modeled with historical data, the most devastating technological losses frequently arose from novel attack vectors, unknown software vulnerabilities, or simple human errors with unexpectedly massive downstream consequences. This “unknown unknown” factor represented the most profound challenge and solidified the view that clear, defensible contracts were the last and best line of defense.