As natural disasters intensify across the United States, homeowners in states like Florida and California are facing unprecedented challenges in securing insurance coverage. Today, we’re speaking with Simon Glairy, a renowned expert in insurance and Insurtech, with deep expertise in risk management and AI-driven risk assessment. With years of experience analyzing trends in disaster-prone regions, Simon offers invaluable insights into the growing crisis of policy non-renewals, skyrocketing premiums, and the broader implications for homeowners and the insurance industry. In this conversation, we explore the reasons behind insurers pulling back, the impact on vulnerable communities, and what the future might hold for property protection in high-risk areas.

Can you walk us through what non-renewal of homeowners insurance policies means and why it’s becoming such a pressing issue in states like Florida and California?

Non-renewal happens when an insurance company decides not to continue coverage for a homeowner at the end of their policy term. It’s different from a cancellation, which can occur mid-term for specific reasons like non-payment. In states like Florida and California, non-renewals are spiking because insurers are grappling with heightened risks from natural disasters—think hurricanes in Florida and wildfires in California. These events are becoming more frequent and severe, leading to massive claims that strain insurers’ financial models. When they can’t predict or absorb the losses, they opt to drop policies in high-risk areas, leaving homeowners scrambling for alternatives, often at much higher costs or with no options at all.

What do the non-renewal rates of 3.35% in Florida and 3.18% in California for 2024 reveal about the health of the insurance market in these states?

These numbers are a red flag for the insurance market’s stability in both states. A non-renewal rate above 3% means a significant chunk of homeowners are losing coverage annually, which isn’t sustainable for communities already under stress from disasters. It signals that insurers are retreating from these markets, viewing them as too risky or unprofitable. This isn’t just a statistic—it’s a sign of eroding trust between insurers and policyholders, and it points to a deeper crisis where the private market is failing to meet the needs of residents in disaster-prone areas, pushing more people toward state-backed plans or leaving them uninsured.

Why do you think non-renewal rates have surged so dramatically since 2018, especially with Florida’s rate jumping 1.7 times and California’s soaring 3.9 times?

The sharp increases reflect a perfect storm of factors. Since 2018, we’ve seen climate change amplify the frequency and intensity of natural disasters—hurricanes in Florida and wildfires in California have caused billions in damages. Insurers are recalculating their risk exposure with every event, and many are deciding it’s not worth staying in these markets. On top of that, regulatory constraints in states like California often limit how much insurers can raise premiums to offset losses, so they exit instead. Reinsurance costs, which insurers rely on to cover big claims, have also skyrocketed, further squeezing their margins and driving these non-renewal spikes.

Louisiana and Washington have seen even steeper increases in non-renewal rates since 2018, up 5.4 times and 4.7 times respectively. What unique challenges or events might be contributing to these trends in those states?

In Louisiana, the massive uptick is largely tied to devastating hurricanes like Ida in 2021, which caused widespread destruction and overwhelmed insurers with claims. The state’s coastal vulnerability and aging infrastructure make recovery slow and costly, deterring insurers from sticking around. Washington, on the other hand, is dealing with increasing wildfire risks, especially in the eastern part of the state, compounded by severe flooding in some areas. These events are less predictable than in traditional high-risk zones, catching insurers off guard. Both states also face issues with limited regulatory flexibility on rate adjustments, making it harder for insurers to balance their books, so they pull out.

Some data suggests that high cancellation rates aren’t due to financial struggles for insurers, given their income growth of 2.6% over six years. If it’s not about profitability, what’s really driving insurers to drop so many policies?

While overall income might be up, the distribution of risk and loss is uneven. Insurers are looking at specific regions or portfolios where claims from natural disasters are wiping out profits, even if their broader financials look stable. It’s a strategic retreat—they’re prioritizing long-term sustainability over short-term gains. Beyond that, there’s a growing reliance on data and predictive models showing that certain areas are becoming uninsurable under current conditions. It’s less about immediate financial distress and more about a forward-looking decision to avoid catastrophic losses down the line, especially in states where they can’t charge premiums that match the escalating risks.

Insurance executives often point to fraudulent claims or insufficient rate hikes as reasons for dropping policies. How much weight do you think these arguments hold, and are there other underlying issues at play?

There’s some validity to their claims, but it’s not the full picture. Fraudulent claims do exist and can inflate costs, especially in post-disaster scenarios where oversight is stretched thin. Insufficient rate hikes are also a real issue in states with tight regulatory caps—insurers argue they can’t price policies to reflect true risk. However, these are often convenient excuses. The bigger issue is the structural mismatch between traditional insurance models and the accelerating pace of climate-driven disasters. Many companies haven’t adapted their underwriting or risk-sharing strategies, so they’re choosing to exit rather than innovate or invest in solutions like better risk mitigation partnerships with governments.

With nearly half of claims denied by some of the largest insurers last year, how does this trend affect homeowners in disaster-prone states?

This high denial rate is devastating for homeowners, especially in disaster-prone states where they’re already at high risk of loss. When claims are denied, people are left to foot the bill for repairs or rebuilding out of pocket, which many can’t afford. It erodes trust in the insurance system—homeowners pay premiums expecting protection, only to be turned away when disaster strikes. This also exacerbates financial inequality, as lower-income households are least equipped to handle unexpected costs. Over time, it discourages people from insuring at all, increasing the number of uninsured properties and amplifying community-wide economic risks after a disaster.

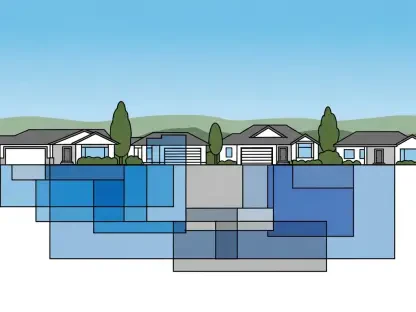

In Florida, active home insurance policies have dropped by 78% over the past decade, and the state’s insurer of last resort now covers 63% of homes. How does this shift impact homeowners seeking coverage?

This shift is a double-edged sword for Florida homeowners. With private insurers pulling out, the state’s insurer of last resort—essentially a safety net—has become the primary option for most. On one hand, it ensures some level of coverage when no one else will step in. On the other, these state-backed plans often come with higher premiums and less comprehensive protection, and they’re funded by assessments on all policyholders, which can drive costs up further. Homeowners are caught in a bind—fewer choices, higher costs, and the constant worry that even this last resort could be overwhelmed by a major disaster, leaving them vulnerable.

Florida’s average home insurance premium has risen 22% after inflation to $3,454 a year. How are these escalating costs reshaping homeownership and affordability in the state?

These soaring premiums are fundamentally altering the landscape of homeownership in Florida. For many, insurance costs are becoming a larger slice of monthly expenses, rivaling or exceeding mortgage payments in some cases. This squeezes budgets, especially for middle- and lower-income families, making it harder to afford a home or maintain one long-term. We’re seeing people delay buying homes, move to less risky (and often less desirable) areas, or go uninsured, which is a huge gamble. It also impacts property values—without affordable insurance, homes become harder to sell, creating a ripple effect on local economies and widening the affordability gap.

Given the warning that one major storm could lead to catastrophic losses for uninsured homes in Florida, what proactive measures do you think homeowners and the state could take to mitigate this looming risk?

Homeowners can start by investing in disaster-resilient upgrades—things like storm shutters, reinforced roofs, or elevated foundations—which can lower premiums and reduce damage. They should also explore community-level solutions, like mutual aid networks for post-disaster recovery. On the state level, Florida needs to bolster its insurer of last resort with stronger financial backing while incentivizing private insurers to return through risk-sharing programs or tax breaks. Public-private partnerships for mitigation projects, like better flood barriers or wildfire buffers, are critical too. Education campaigns on the importance of coverage, even at high costs, could also help reduce the uninsured rate before a major storm hits.

Looking ahead, what is your forecast for the future of home insurance in disaster-prone states like Florida and California over the next decade?

I expect the challenges to intensify over the next decade unless there’s significant intervention. Climate change will likely drive more frequent and severe disasters, pushing non-renewal rates and premiums even higher in states like Florida and California. We may see private insurers continue to retreat, with state-backed plans bearing an unsustainable burden. Without innovation—such as AI-driven risk assessment to better price policies or federal support for catastrophe funds—the market could collapse in some areas, leaving millions uninsured. On the flip side, there’s potential for growth in alternative models, like parametric insurance, which pays out based on disaster triggers rather than damage assessments. But it will take bold policy changes and industry adaptation to turn this crisis around.