Welcome to an insightful conversation with Simon Glairy, a leading expert in insurance and Insurtech, renowned for his deep expertise in risk management and AI-driven risk assessment. With a career dedicated to understanding and mitigating the financial impacts of natural disasters, Simon has been at the forefront of catastrophe modeling innovations. Today, we dive into the lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina, the evolution of risk assessment tools, and the pressing challenges that still loom over the industry as climate change and population shifts heighten the stakes of natural disasters.

Can you take us back to 2005 and explain what went wrong with catastrophe models during Hurricane Katrina?

Absolutely. Hurricane Katrina was a wake-up call for the insurance industry. The models at the time significantly overestimated the strength of the levees protecting New Orleans, assuming they could withstand a Category 3 storm. They also failed to adequately predict the devastating impact of storm surge, which ended up being the primary driver of destruction as massive waves overwhelmed the city. Another major blind spot was the underestimation of exposure for commercial properties—data on their locations and values was often incomplete or inaccurate, leading to massive miscalculations of potential losses. It exposed how much we relied on assumptions rather than robust data.

How have these models evolved in the nearly two decades since Katrina struck?

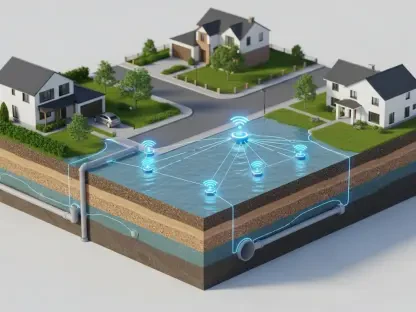

The progress has been remarkable. Computing power has skyrocketed, allowing us to run complex simulations that were unimaginable back then. We now use granular, asset-level data to assess risks with much greater precision, down to individual properties in some cases. AI has also been a game-changer, helping us analyze vast datasets, identify patterns, and refine predictions, especially for elements like storm surge that were once overlooked. The models today aren’t just more powerful; they’re built on a deeper understanding of how multiple factors interact during a disaster.

What do you see as the biggest hurdles still facing catastrophe modeling?

There are several, but one standout is the difficulty in predicting secondary perils like tornadoes, hailstorms, and floods. Unlike hurricanes or earthquakes, these events are less consistent in their patterns and harder to pin down with historical data. Recent storms, like Hurricane Helene, have shown how current models can falter with unexpected inland flooding in areas not traditionally seen as high-risk. Another challenge is modeling risks for individual properties in less vulnerable zones—without good data or clear risk profiles, insurers struggle to price coverage accurately, and homeowners often skip it altogether.

How have economic trends and demographic changes increased the financial risks of hurricanes?

The financial stakes are much higher now. Coastal areas have seen a huge influx of people, and the homes being built there are far more expensive to repair or replace than they were 20 years ago—think luxury features and larger footprints. Inflation has compounded this, driving up costs for materials and labor, which hits both insurers and homeowners hard. More people in harm’s way means potential losses from a single storm could be catastrophic, far exceeding what we saw with Katrina when adjusted for today’s values.

In what ways is climate change reshaping the landscape of hurricane risk?

Climate change is a massive factor. Higher temperatures are expected to fuel more intense hurricanes, packing stronger winds and heavier rainfall. Rising sea levels amplify storm surges, making coastal areas even more vulnerable to flooding. These shifts could lead to insured losses that dwarf historical figures in the coming years. We’re not just talking about more frequent storms, but storms that hit harder and cause damage in ways we’re still trying to fully understand and model.

Why does the industry still struggle with accurate loss estimates for commercial properties?

It comes down to data quality—or the lack of it. Even today, the exposure data for commercial properties provided to models is often incomplete or outdated. Locations might be miscoded, and property values are frequently understated. This gap means that when a major disaster hits, the losses can be a nasty surprise for insurers and their clients. It’s a tricky issue because better data could lead to higher premiums, which might deter coverage, but without it, we’re flying blind.

What’s your forecast for the future of catastrophe modeling in light of these ongoing challenges?

I think we’re at a pivotal moment. The next decade will likely see even tighter integration of AI and real-time data, which could help close some of the gaps we’ve discussed, especially for secondary perils and commercial exposures. But it’s not just about tech—collaboration between insurers, policymakers, and scientists will be crucial to address systemic issues like climate change and urban sprawl in vulnerable areas. I expect models to become more predictive than reactive, but only if we commit to improving data quality and adapting to a rapidly changing environment. The stakes couldn’t be higher.